Lost Traditions

Lost Traditions

Explore Shocker Lost Traditions

Have you heard the story about Lincoln LaPaz and the Jinx Gang? Or the rumors about which campus buildings are haunted? Read on for more about traditions now gone, but not forgotten.

Operation Egghead

In February 1959, “Operation Egghead” was begun. Sponsored by the women of Mortar Board, Operation Egghead, or Egghead Week, was initiated for the purpose of celebrating academic accomplishment and activity. During Egghead Week, the focus was on such academic endeavors as encouraging all students to raise their grades and promoting all kinds of scholarly lectures and other studious activities. The five-day event featured “fireside chats” with faculty members at participating Greek houses and dormitories, numerous book and film reviews and a special convocation, “Select-A-Lecture, ” which showcased simultaneous lectures by outstanding professors on campus. The week was all about “saluting superior students,” and one of its key events was a scholarship breakfast that served to honor students who had achieved an overall GPA of 3.7 or higher. President Lindquist addressed the students in attendance at the 1964 breakfast.

May Day Celebration

Dating back to at least 1912, students were known to gather outside their Fairmount College classrooms for an afternoon of May Day festivities. They began with a picnic lunch, took an hour rest and then participated in athletic events before what were surely the two highlights of the day: the coronation of the May Queen and her court—and wrapping the maypole in black and yellow ribbon. Through the years, the May Day celebration blossomed into a full day of special activities that included athletic competitions, including tug-of-war and broom hockey contests. The day traditionally ended with decorating the maypole.

In 1928, the year Hippodrome began on campus, it was the May Queen who presented the trophies to the winners of the skits. More than three decades later, May Day was still adding activities to its “play list.” In the 1960s, a May Day dance was added and held in the Bluenote Ballroom and Mortar Board made the selection of eligible junior women into the organization another featured happening on May Day.

Special Places on Campus

Interestingly enough, a number of trees have served as landmarks for the students of our Shocker past. These students often left their

marks by carving their names into wooden benches under special campus trees or having photos made of themselves at their favorite

campus places.

One example of our tree-ful history is this: Students in a Fairmount College literature class were so moved by one of the Shakespeare plays that the professor taught that year, that they planted a tree near the library. They named it the “Shakespeare Tree.”

Another tree with a special place in Shocker lore is the one whose trunk was encircled by the Spoonholder, a popular wooden bench where students met for conversation and to relax and study. Designed by Elizabeth Sprague, a Fairmount College art professor, the Spoonholder was created as an art installation. Located in the middle of campus near Fairmount’s two most prominent buildings, Fairmount Hall and Morrison Library, the bench became especially known as a meeting place for Fairmount couples to enjoy some alone time with each other.

Our third Shocker tale of trees goes all the way back to the first president of Fairmount—Nathan J. Morrison, who was an 1853 graduate of Dartmouth with ties to another Dartmouth grad, the U.S. politician Daniel Webster. In order to “spruce up” the largely treeless 20-acre prairie campus of early Fairmount College, Morrison took up the role of prairie tree farmer and had elms and later evergreens shipped from Webster’s New England tree farm at the turn of the 20th century. The elms and evergreen trees, which were planted on campus by members of Webster Society, grew up to become Webster Grove. In 1923, members of the Men of Webster fraternity added a bench to the campus scene. This Men of Webster bench became known for the student carvings it held. Long after the bench and most of the trees in Webster Grove were gone from campus, a university historian determined that three century-old evergreens located south of Wilner Auditorium might be from Webster’s farm.

In the early days of our campus, a few other special locations where students would gather and spend time together included the Cinder Path, the Tower and the Conservatory Balcony.

Haunted Buildings

With our campus being as old as it is, stories of ghost sightings and other bizarre paranormal happenings are sure to find their way into Shocker lore—and they have! Strange phenomena, including flickering lights and mysterious sounds and voices, have been reported in a number of our campus buildings. Old Memorial Gymnasium, later renamed Henrion Gymnasium and now Henrion Hall, which is used as studio space for ceramics, sculpture and painting; the old Auditorium and Commons Building, now Wilner Auditorium; and Fiske Hall make the Top Three on Wichita State’s haunted buildings list.

Henrion Hall is said to be haunted by the ghost of a maintenance worker who was fatally electrocuted while working in the building one fateful day in the 1950s. The stories say that his spirit never left. Some ghost hunters claim to have seen his shadow either late at night or in the early hours of dawn.

Wilner Auditorium is said to be home to the ghost of George Wilner himself, the building’s namesake. Wilner became the head of speech and theater at Fairmount College in 1923 and, after a long and productive career, retired from the University of Wichita in 1960; he passed away in 1976. Wilner was extremely active on campus and loved the theater. He is said to be a friendly ghost who roams the halls to make sure that the building is kept in tip-top condition. He opens and closes doors, talks to himself and checks the light bulbs!

Fiske Hall, the oldest building on campus, has no identifiable ghostly presences—although bizarre happenings have been reported. Through the years, the building has served as a men’s dormitory, an infirmary during the 1918 Influenza Epidemic, classrooms and now houses the departments of history and geography, philosophy and international programs.

If you dare to meet them, gather a group of friends and see if you can catch a glimpse of George, the friendly ghost, in Wilner Auditorium or the unnamed ghost of Henrion Hall. Who knows, they might just have more of their stories to tell you!

1971 – 1995: Game Day Walkouts

Initially started when students walked out of the stadium after a great football victory to celebrate together, this tradition took on a life of its own and developed into a game day event. In preparation for these walkouts, held before the game, selected students would get up early and write the time of the walkout on campus sidewalks. Students would proceed to class and then near the end of class get up and leave.

The marching band would be playing pep songs, the cheerleaders would be leading chants and the Wheaties would be making sure everyone’s excitement level was high. Mass chaos would ensue for about the first 15 minutes while the assembled students decided where to hold their pep rally. Campus streets were filled and classrooms were empty!

This tradition lasted until the administration and deans got involved. They decided that walkouts were only to be held once a year. Accordingly, the walkouts were transformed into an annual Rally Day by the Pep Council in the late 1960s.

The Stone Jinx and the Jinx Gang

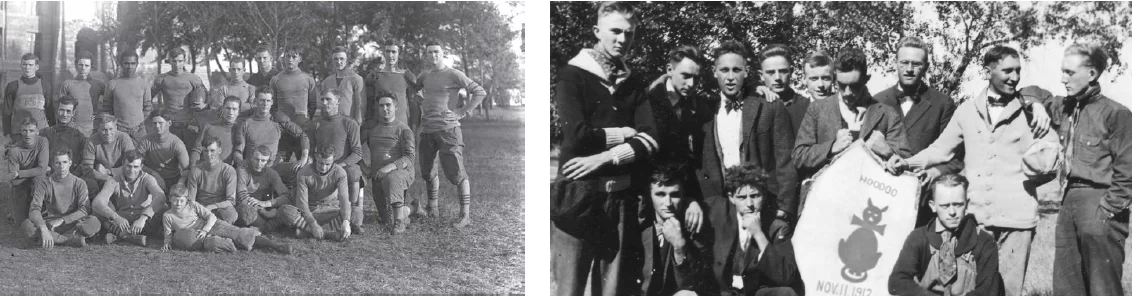

The tale of the Stone Jinx begins back in November 1912, when the Southwestern College Moundbuilders of Winfield trounced the Fairmount Wheatshockers 41- 3 in football. The story goes that the Moundbuilders were overjoyed and decided to memorialize the victory. They selected a stone, in the shape of a tombstone, near their campus and painted a grinning black cat clad in the black and yellow of Fairmount College with the date and score of the football game. They placed the stone in a Winfield graveyard.

Fairmount students simply laughed off the stone. They certainly didn’t attribute any hoodoo powers to it— not until the following year when the Wheatshockers again lost to the Moundbuilders 29-7. Spurred to action, a group of Fairmounters traveled to the Winfield graveyard to take possession of the stone, escaping back home on a Wichita-bound train. Their goal was to destroy the hoodoo stone, but before this could be accomplished, the Moundbuilders stole the Stone Jinx back.

The Jinx was held in a locked vault for three years on Southwestern’s campus. Those three years saw Wichita’s defeat at every football game against the Moundbuilders. Then in fall 1917, it was time for Fairmount to retaliate and the Jinx was returned to Wichita by means of a carefully planned out raid. With the return of the Jinx, it was decided among the students that guards were needed to make sure it wouldn’t return to the enemies. Led by Fairmount student Lincoln LaPaz, “The Jinx Gang” was created with 12 boys and one girl. Membership and initiation was top secret and the total number of members was kept at 13. The Stone Jinx raids grew ever more elaborate and, thus, more dangerous for both Wheatshocker and Moundbuilder students; they were eventually forbidden in the early 1920s.

We have no record of where the Jinx ended up. It was said to have been “doomed to a psychological death.” Yet rumors persist that LaPaz, who would go on to become a noted astronomer and pioneer in the study of meteors, actually led a group of Fairmounters in finally accomplishing that earlier mission of destroying the Jinx. It’s said, variously, that they smashed it to smithereens—or blew it up sky high!